A practical, stage-wise approach from first-trimester screening to fetal cardiology decision-making

Introduction

Mild tricuspid regurgitation (TR) is a common finding in fetal imaging and a frequent source of uncertainty. With improving ultrasound resolution, small TR jets are now detected routinely, yet their clinical significance varies widely.

In early pregnancy, when tricuspid regurgitation is detected in the presence of other trisomy markers, it significantly increases genetic risk and warrants careful genetic evaluation. In contrast, when TR is identified in the absence of genetic markers, so-called isolated tricuspid regurgitation, the clinical focus shifts away from aneuploidy and toward the possibility of congenital heart disease, functional impairment, or altered cardiac loading.

The primary emphasis of this blog is on the assessment and interpretation of isolated tricuspid regurgitation, as this is where uncertainty most commonly arises in day-to-day practice.

A clear distinction between tricuspid regurgitation associated with trisomy markers and truly isolated tricuspid regurgitation is essential, as management strategies and clinical implications differ fundamentally between the two.

1. Tricuspid regurgitation in the first trimester: a screening marker, not a diagnosis

At 11–13 weeks’ gestation, tricuspid regurgitation should be viewed strictly as a screening marker. Its role at this stage is to modify risk assessment, not to establish a cardiac diagnosis.

Several features of early TR deserve emphasis:

- Mild TR is relatively common in early gestation

- It may be transient and resolve on follow-up

- It often reflects the physiological loading conditions of the developing right ventricle

The purpose of identifying TR at this stage is therefore triage, not labelling. Once detected, the clinician’s task is to place it correctly within the overall screening context before deciding on escalation.

In cases where TR is isolated, with otherwise reassuring first-trimester findings, it should not be interpreted as evidence of structural heart disease or cardiac dysfunction. Instead, it serves as a prompt for systematic reassessment and planned follow-up, rather than immediate diagnostic conclusions.

The key question in the first trimester is not “What is the diagnosis?” but rather:

“Does this finding alter risk sufficiently to justify further evaluation at this stage, or can it be safely observed?”

This distinction underpins all subsequent decision-making and prevents premature or unnecessary escalation.

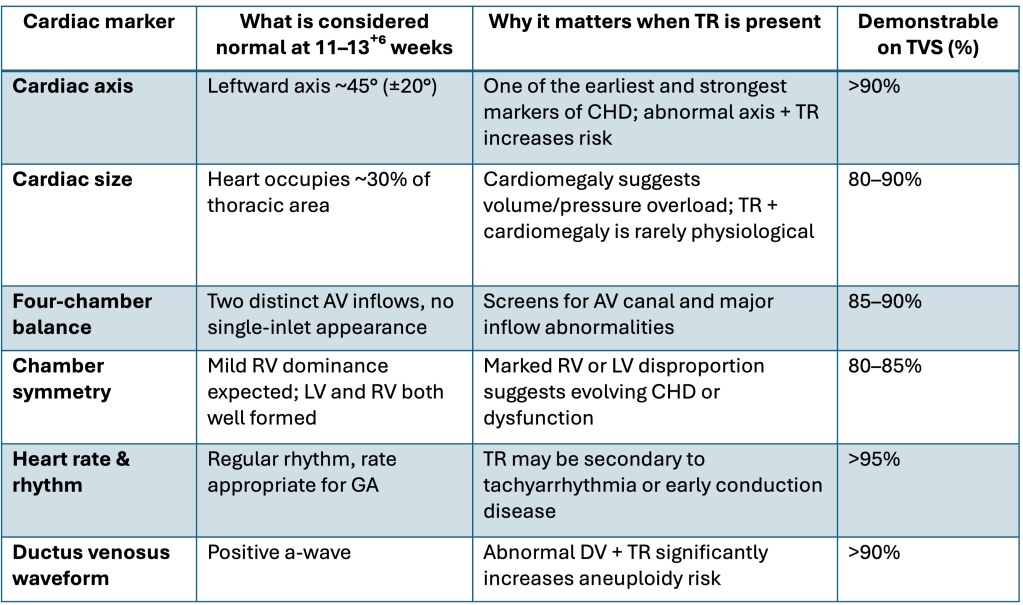

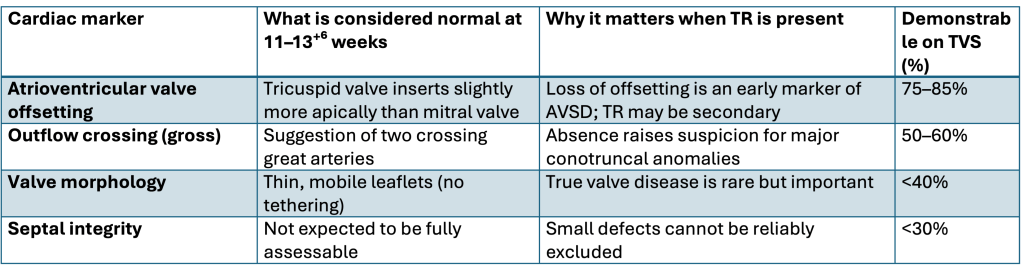

These markers are:

- Feasible in the majority of good-quality TVS scans

- Highly informative

- Independent of whether TR is present or not

When TR is detected, these same markers become even more important.

3. Beyond basic screening: early-trimester cardiac markers

If a TR jet appears in the first trimester, conduct a targeted cardiac sweep to identify concerning patterns rather than diagnose. Some markers can be reliably assessed early; others are limited and shouldn’t be overinterpreted. The key is knowing which observations are dependable at this stage.

To keep early screening safe and practical, it is equally important to state what should not be expected at 11–13⁺⁶ weeks:

- Detailed valve morphology

- Septal defect diagnosis

- Quantitative ventricular function

- Outflow tract gradients

4. The diagnostic gap (12–18 weeks): managing uncertainty pragmatically

An often underappreciated yet critical component of TR management is the waiting period.

In clinical practice:

- TR is frequently identified at 12–13 weeks gestation.

- Definitive fetal echocardiography typically yields accurate results only at 18–20 weeks, except in mothers with a lean body habitus.

- Most fetal cardiologists do not routinely utilize transvaginal fetal echocardiography.

This sequence of events leads to a diagnostic gap, which requires careful management and consideration.

The most practical strategy

A repeat targeted scan at 14–16 weeks is often the single most useful step.

The aim is not a detailed diagnosis, but to assess:

- Persistence or resolution of TR

- Evolution of other cardiac or extracardiac markers

- Resolution of TR strongly favours a physiological phenomenon

- Persistence of TR prompts re-evaluation of overall risk

This simple step prevents both premature reassurance and unnecessary escalation.

5. Genetics in Isolated TR

Genetic evaluation should be guided by overall aneuploidy risk, not by tricuspid regurgitation alone.

When genetics should be considered

In the first trimester, genetic escalation is appropriate when tricuspid regurgitation is not isolated, and is accompanied by one or more established trisomy markers, such as:

- Increased nuchal translucency

- Abnormal ductus venosus waveform

- Extracardiac anomalies or additional soft markers

In this context, tricuspid regurgitation acts as a risk amplifier, strengthening concern raised by other markers.

When tricuspid regurgitation is truly isolated, it should not prompt genetic testing. In such cases, tricuspid regurgitation is best regarded as a functional or physiological finding, and management should focus on follow-up rather than invasive evaluation.

6. Special situations that modify interpretation

Certain contexts deserve explicit mention because they alter how TR should be viewed.

Monochorionic twin pregnancies

In monochorionic twins, even mild TR may reflect early inter-twin hemodynamic imbalance rather than intrinsic valve pathology. The threshold for closer surveillance should therefore be lower.

Abnormal ductus venosus

Among all first-trimester markers, ductus venosus flow is the most powerful functional discriminator. TR associated with an absent or reversed a-wave is rarely physiological and warrants escalation.

Rhythm abnormalities

Early rhythm disturbances can produce secondary TR. Rhythm assessment should always accompany TR interpretation.

These situations do not require extensive discussion but acknowledging them prevents misinterpretation.

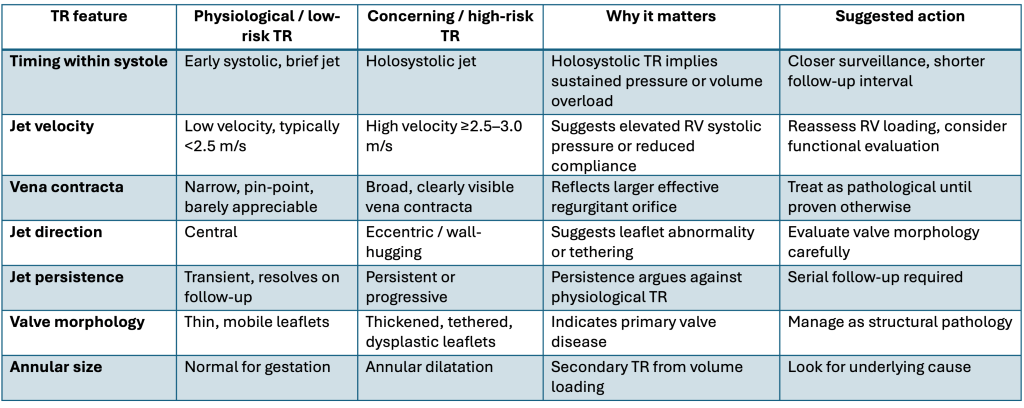

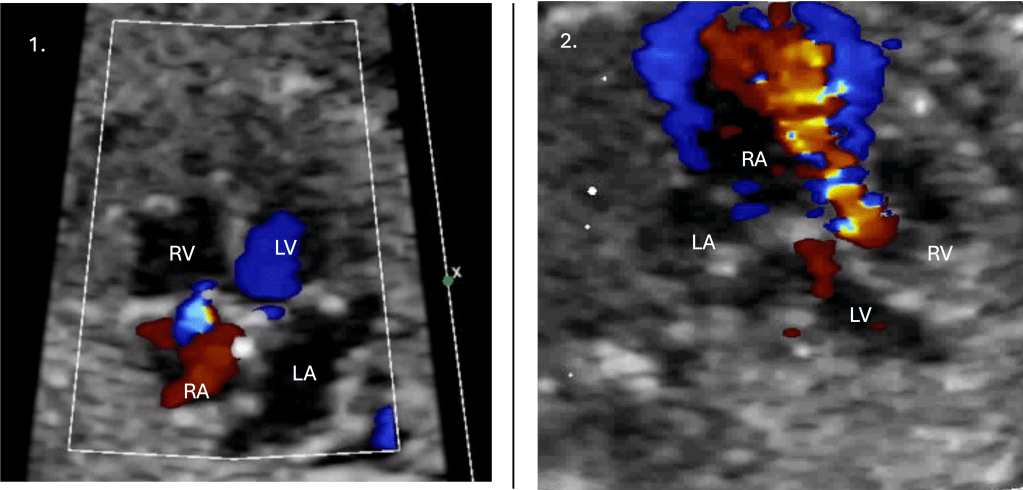

7. Tricuspid regurgitation on fetal echocardiography

At this stage, the Fetal cardiologist evaluates:

- TR characteristics (timing, velocity, jet morphology)

- Valve appearance

- Hemodynamic context (chamber size, cardiomegaly, venous Dopplers)

Earlier studies have used lower velocity thresholds (e.g.,>2.0 m/s) to define non-trivial tricuspid regurgitation; in contemporary practice, a higher threshold (≈2.5 m/s) is more useful for distinguishing physiological jets from those that may reflect increased right ventricular pressure.

8. When anatomy is normal, but TR looks ‘high risk’

It is critical to define high-risk TR features, such as: Four important features are

- Holosystolic timing

- High-velocity jet

- Eccentric jet

- Persistence over time

In these cases:

- TR should not be dismissed as physiological

- The finding warrants closer surveillance

- An extended ventricular functional assessment may be considered, and a review Fetal Echo should be planned to assess a developing lesion or missing rhythm disorder, even when the anatomy appears normal.

9. Likely fetal echo diagnoses associated with TR

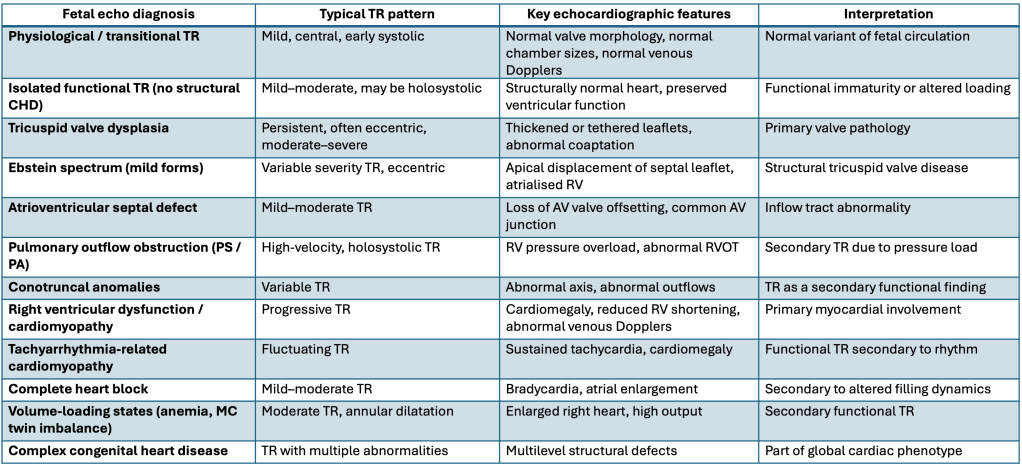

Following fetal echocardiography, TR is most commonly classified as physiological or functional. TR is rarely the diagnosis itself; the diagnosis lies in identifying the underlying cause or confirming its absence.

10. Fetal TR, Outcome and Evidence

The majority of fetuses with isolated mild TR and a normal fetal echocardiogram have an excellent prognosis, with resolution or persistence without clinical significance. Outcomes depend primarily on associated conditions rather than TR severity alone. Structural valve disease, ventricular dysfunction, or complex congenital heart disease represent a minority of cases but require tailored follow-up.

1) First-trimester TR in a high-risk referral population (11–14 weeks)

Huggon et al. (2003) studied fetuses referred for early fetal echo in a predominantly high-risk group (mostly increased NT). Key numbers among fetuses with TR:

- 83% had a karyotype abnormality

- 57% had structural heart disease (in those with TR)

“In early high-risk referrals, TR is frequently associated with chromosomal and/or structural cardiac disease.”

2) Mid-gestation TR with normal heart anatomy on indicated fetal echo referrals

Respondek et al. (1994) reviewed 733 singleton fetuses referred for routine fetal echo and looked at TR with normal anatomy:

- TR prevalence: 6.8% within that referral cohort

- 80% “trivial” TR (non-holosystolic; max velocity <2 m/s)

- 20% “significant” TR (holosystolic; max velocity >2 m/s)

- With Significant, a likely contributing association/cause, such as altered loading conditions or rhythm issues, could be identified in 92%; 8% were “idiopathic”

- Crucially, neonatal follow-up in this cohort was unremarkable.

This supports the concept that most mid-gestation TR detected on fetal echocardiography represents a functional rather than pathological finding.

3) Second-trimester “transient TR” in otherwise normal pregnancies

Clerici et al. (2019) (prospective; 20–23 weeks in 675 pregnancies with normal anatomy/growth):

- TR prevalence 4.74%

- Majority non-holosystolic (87.5%)

- Most had a max velocity <2 m/s

- TR resolved by ~29 weeks in all cases, with no apparent pathological significance reported

This supports the concept of a common benign functional TR phenotype in mid-gestation with normal cardiac anatomy.

4) Postnatal “what diagnoses appear later?” after isolated mild second-trimester TR

Zhou et al. (2021)evaluated isolated mild TR at 18–24 weeks and found:

- No major cardiac disorders postnatally

- Only some minor findings (e.g., small VSD, PDA, PFO/ASD combinations) were higher in the TR group

This supports that isolated mild mid-trimester TR does not translate into major postnatal cardiac disease.

Taken together, these datasets show a clear gradient:

- Early gestation + high-risk referral → TR frequently accompanies chromosomal or major cardiac disease

- Mid-gestation echo referrals with normal anatomy → TR is usually functional and benign

- Unselected normal pregnancies → TR is often transient and resolves

- Postnatal follow-up of isolated mild TR → major pathology is rare

11. A practical decision framework

Conclusion

Isolated mild tricuspid regurgitation is not a problem to be solved, but a signal to be interpreted. Its significance depends on timing, associations, and persistence rather than on its mere presence.

When approached systematically, with clear separation between genetic risk assessment and cardiac evaluation, isolated mild tricuspid regurgitation rarely predicts adverse outcomes. More often, it challenges clinicians to exercise judgement, knowing when to escalate and when reassurance is sufficient.