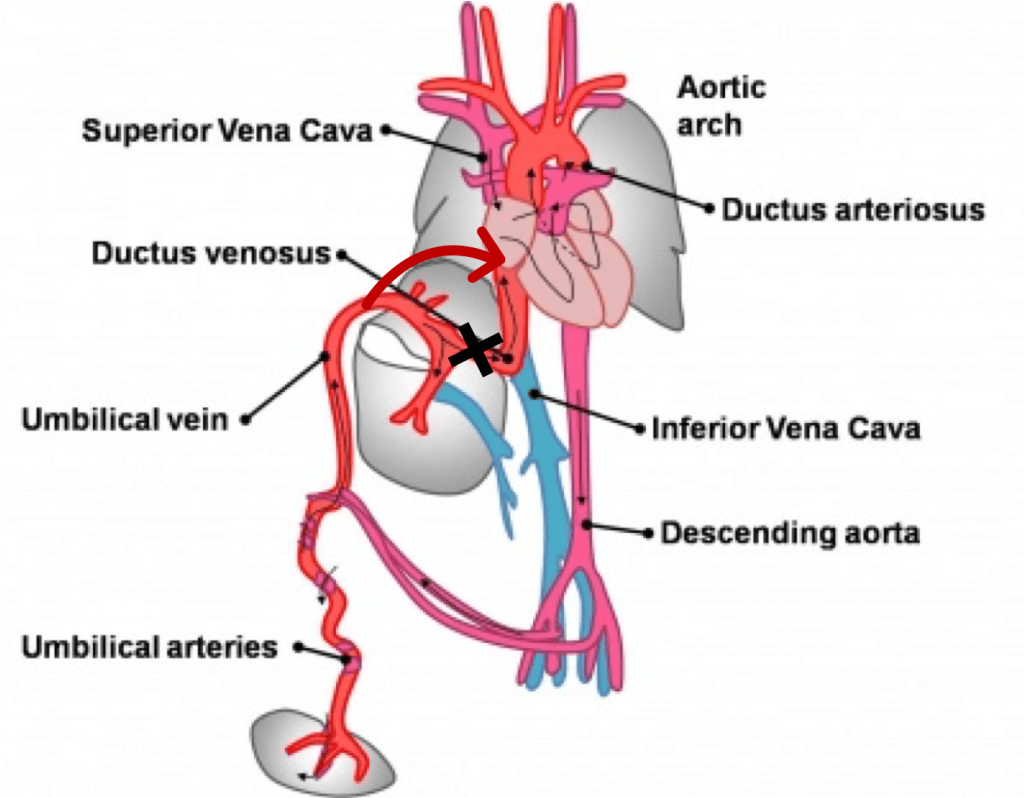

Ductus venosus (DV) is one of the three shunts that are essential for differential oxygen organ-specific delivery adjustment during fetal circulation throughout intrauterine life.

The assessment of the DV flow pattern is now routine and vital part of first-trimester screening ultrasonography, looking for abnormal reversal (‘true’ A wave). Flow reversal has been shown to be associated with cardiac defects and chromosomal abnormality.

Physiology of Ductus Venosus

The narrowed DV regulates blood flow and under normal conditions, allows 20–30 % of the oxygenated umbilical venous return to bypass the liver and portal venous circulation and enter the proximal IVC. This partial flow across the DV allows sufficient pressure to build up at the portal vein, required for the growth of the portal system. Also, the restriction does not allow the direct transfer of umbilical and portal pressure to the cardiac system, thus helps in maintaining the central venous pressure (CVP).

Thus, when the DV is large (the shunt diameter was equal to or larger than the umbilical vein diameter), there could be poor development of the portal system to the extent of CAPVS (congenital agenesis of the portal venous system). Also, there is a possibility of increased CVP due to increased pressure transfer to the cardiovascular system and thus leading to cardiomegaly and heart failure.

Excessive restriction of DV has its implications. This can lead to an increase in pressure in the portal and umbilical veins. The fetus with increased umbilical venous pressure could have a vulnerability when facing hypoxemic states. It can also be the primary cause of fetal hypoxia as the obstruction of the placental venous flow return can result in placental edema and impaired gas exchange. This edema also reduces the transfer of proteins across placenta which in turn may contribute to a decrease in fetal plasma protein levels, one of the causes of the development of hydrops fetalis

Absent Ductus Venosus (ADV)

The Absent Ductus venosus is the complete absence of Ductus venosus communication between portal–umbilical venous system and the hepatic–systemic venous system. With ADV, there are two possibilities for umbilical vein drainage- intrahepatic shunt and extrahepatic shunt. The ratio of extrahepatic to intrahepatic connection is approximately 60:40 in various studies.

ADV with Intrahepatic shunt

In Intrahepatic shunt, all umbilical venous flow to the portal system but no direct communication with IVC, thus all the umbilical venous flow through portal system and then return through hepatic vein after passing through hepatic radicals.

ADV with Extrahepatic shunt

In the extrahepatic shunts, there are different possible connections between the umbilical vein and the venous system:

- direct connection to the right atrium (RA) or through a dilated coronary sinus (CS)

- left atrium

- umbilical vein drains directly into the inferior vena cava

- umbilical vein drains directly into the superior vena cava

- umbilical vein drains into the left, right or internal iliac vein

- umbilical vein shows a direct connection into the renal vein

- umbilical vein shows direct connection into the right ventricle

When such an ‘extrahepatic’ aberrant vessel is present, the flow into the entire portal system depends on the volume shunted through the aberrant vessel.

Associations with ADV

In various studies, the incidence of associated significant structural or chromosomal anomalies with ADV is between 40-50 %, with no significant difference between Intrahepatic or extrahepatic shunt types. There is an association shown with Turner or Noonan syndromes as well as trisomy. The poor perinatal outcome is associated with structural or chromosomal anomaly with ADV.

Pathophysiology of ADV

The pathology of the development is similar to large ductus venous communication for large extrahepatic shunt, leading to decreased flow through the portal system and thus higher incidence of CAPVS and other portal anomalies. Also, they have a higher incidence of cardiomegaly and high output cardiac failure due to increased shunt and pressure through the shunt. Thus, causing hydrops.

The Pathology in intrahepatic shunt is similar to restricted DV flow. Thus, the incidence of placental edema, causing hypoproteinemia in the fetus and thus can cause hydrops. Also, have an issue with perinatal hypoxia for the same reason.

Isolated ADV

Isolated ADV (with no associated with structural or chromosomal anomaly) has a better outcome; caution is required over the antenatal period, as the hydrops may develop at a later stage as well. Postnatally it is required to careful assessment of portal venous system as well as the persistence of aberrant communication between the portal and systemic venous system (Abernathy malformation).

Conclusion

Ductus venosus flow assessment is an integral part of the assessment of fetal wellbeing. ADV is a well-recognized entity and not commonly diagnosed with or without associated chromosomal abnormality. ADV, with associated with the structural or chromosomal anomaly, has a poor fetal outcome. Isolated ADV has a good fetal outcome; however, it has the propensity to develop cardiomegaly, fetal hypoproteinemia, and hydrops. Thus, these fetuses require frequent fetal assessment as well as fetal echocardiography during the second trimester and also later as required. After delivery, careful assessment for portal system hypoplasia and the aberrant connection is required.